I know it's been quiet here. I got clobbered by the semester, which ends in about three weeks. Watch this space.

|

Pop Matters has posted an excerpt from the book. Enjoy this free sample!

I know it's been quiet here. I got clobbered by the semester, which ends in about three weeks. Watch this space.

0 Comments

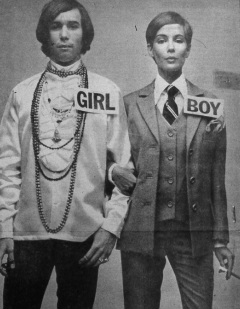

If you asked someone in the fashion industry, unisex was a fad that came and went in one year: 1968. For that brief moment, the fashion press hailed gender blending as the wave of the future, and department stores created special sections for unisex fashions. Most of these boutiques had closed by 1969. However, in the more mainstream realm of Sears, Roebuck catalogs and major sewing patterns, “his ‘n hers” clothing – mostly casual shirts, sweaters and outerwear – persisted through the late 1970s. The difference between avant-garde unisex and the later version is the distinction between boundary-defying designs, often modeled by androgynous-looking models, and a less-threatening variation, worn by attractive heterosexual couples. Also: one more chapter to go! Huzzah!!!

I'm about to ask some messy questions. Writing about gender can get that way. In 1967, cultural critic Russell Lynes observed that the gender-bending styles of the young had a curious effect. in his opinion, the new fashion of women dressing more like boys or men helped homely girls look more attractive. Lynes gives the example of Barbra Streisand, but his comment reminds me of the recent viral video of the Dustin Hoffman interview about his cross-dressing experience in "Tootsie". Nearly 40 years later, Hoffman is reduced to tears with the recollection that the make-up people had made them as pretty as they could, and he couldn't measure up to his own standards of a woman worth spending time on. Then I am reminded of a recent conversation with a colleague who knows a bit about the subject -- she's taught a course on the history of drag -- where she mused about the relative "success" of male-to-female gender performance, compared to women attempting to pass as men. Here's the question: Do men find otherwise plain or unattractive women look more attractive -- as women -- when they wear masculine clothing? Is feminized men's clothing more threatening than mannish styles for women in our culture because it is a challenge to the existing power structure, or because the artifice involved in performing femininity -- make-up, body shaping and elaborate hair modification -- is exposed as the trickery it really is when a man does it? What are the limits of beauty culture, and how do girls and women negotiate their own sense of self worth within those limits? Do we experience a Tootsie moment when we know we look our best and know deep in our souls that it isn't "enough"? What does it feel like? Personally, it feels like my own personal cloak of invisibility. I can look quite presentable when I try, and I do still enjoy the effort. But I can also choose, when I feel like it, to pull on something comfortable, skip the makeup and enjoy the sensation. Oddly enough, androgynous clothing helps me do that. P.S. Getting dragulated by RuPaul is still on my bucket list I've been collecting dozens -- no, make that hundreds -- of images as part of my research and I want to share them with you all, because they are fun, thought-provoking and even astonishing.

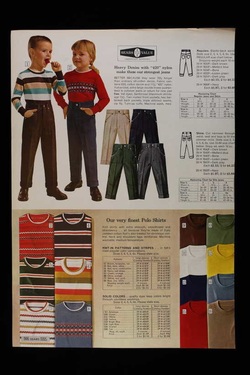

They are all here on my new Tumblr, Gender Mystique. Enjoy! As I finish the chapter on children's clothing, I'm sorting through my images and videos about adult fashions. Here's one you'll enjoy, from an early Soul Train episode. Notice the range of gender expression, on both men and women. A thought: did African American men have more or less leeway in this realm than white guys? My first impression is more, but also that I may be dazzled by the flashiness.  ... protounisex? In every Sears catalog from the 1950s and early 1960s, there were several pages of neutral play clothes for boys and girls in the size 2-6X range. They are pretty much boys' clothes in a variety of colors, but they are modeled by girls as well as boys with not a peep of comment in the catalog copy. This example is from fall, 1964, but typical of styles worn by children for years before "unisex" fashion was invented. Before you start thinking how awesomely gender-free we were back then, keep in mind that this is also the "Mad Men" era and the year after The Feminine Mystique rocked the domestic scene. So why was boyish clothing for girls ok? And why did unisex clothing for adults seem so revolutionary?  I came across some interesting thoughts on unisex fashion in "Looking Good", published in 1976. The author, Clara Pierre, was writing from the perspective of an industry insider observing what she expected to be permanent changes in fashion. In chapter 10 "From bralessness to unisex", she explains the connection between sexual liberation and unisex clothing as a process of increasing comfort various aspects of sexual identity and expression: "for whatever reason, we began to feel more comfortable first with sex pure and simple, then with homosexuality and now with androgyny" That was then and this is now, as they say. Clearly, some people thought that the culture wars over sex was over, even as it was just beginning. So, I wonder: what happened? I am nearly finished with the proposal for the next book, on unisex trends from the late 1960s through the mid-1980s. Thanks to the fashion cycle and “That Seventies Show”, the superficial outlines of these trends are fairly familiar to the general public. As usual, my intent is to reveal how complicated the movement was (and I chose that word intentionally.).  The unisex movement – which includes female firefighters, Roosevelt Greer’s needlepoint and “Free to be…You and me” -- was a reaction to the restrictions of rigid concepts of sex and gender roles. Unisex clothing was a manifestation of the multitude of possible alternatives to gender binaries in everyday life. To reduce the unisex era to long hair vs. short hair, skirts vs. pants and yes, pink vs. blue is to perpetuate that binary and ignore the real creative pressure for alternatives that emerged during this period. But what alternatives were posed, and why? For the most part, unisex meant more masculine clothing for girls and women. Attempts to feminize men's appearance turned out to be short-lived, not permanent changes. The underlying argument in favor of rejecting gender binaries turns out to have been another binary: a forced decision between gender identities being a product of nature or nurture. For a while, the "nurture" side was winning. Gender roles were perceived to be socially constructed, learned patterns of behavior and therefore subject to review and revision. Unisex fashions were one front in the culture wars of the late 60s and 70s -- a war between people who believed that biology is destiny and those who believed that human agency could override DNA.

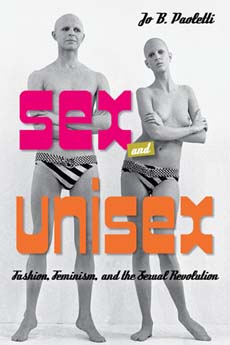

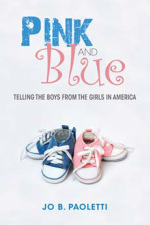

The working title is “Sex and Unisex: The Unfinished Business of the 1970s”. Because it’s clear to me from today’s culture wars that the sexual revolution is turning out to be more like the 100 Years War. One of the most iconic works of the unisex era is Lois Gould's short story, "X: a fabulous child's story", a tale of an "Xperiment" in gender-free child-raising. It first appeared in Ms. in 1972, and was expanded into an illustrated children's book in 1978. (The Gender Centre in Australia has the story online.)  Here's a quick summary: A baby is born to two parents who have agreed to keep its sex a secret, as part of a huge, very expensive scientific experiment. They are given a thick handbook to help them navigate future problems, from how to play with X to dealing with boys' and girls' bathrooms at school. While other adults react with hostility, X's schoolmates eventually start imitating its freedom in dress and play. Finally, the PTA demands that X be examined, physically and mentally, by a team of experts. If X's test showed it was a boy, it would have to start obeying all the boys'rules. If it proved to be a girl, X would have to obey all the girls' rules. And if X turned out to be some kind of mixed-up misfit, then X must be Xpelled from school. Immediately! And a new rule must be passed, so that no little Xes would ever come to school again. Of course, X turns out to be the "least mixed up child" ever examined by the experts. X knows what it is, and "By the time it matters which sex X is, it won't be a secret any more". Happy ending. Ah, the 70s! Between this story, Harry Nilsson's "The Point" and "Free to be You and Me", the future looked so clear and bright. What happened? I will be taking a close look at the vision in each over the next week and discussing here, but would love to hear your memories and reactions. I am currently caught between two books. "Pink and Blue" is out in the world, and that means interviews and conversations about gender differences in children's clothing. But I am also working on the proposal for my next book, which will be about unisex clothing (roughly 1965-1985). In terms of historical description, it looks like it will be pretty straightforward. Women and girls started wearing pants, even to work and school. Men enjoyed a brief "peacock revolution", when bold colors and pattern returned to their wardrobes. Legal battles were fought over hair (hair!): soldier's hair, students' hair, firefighters' hair. It was hard to tell the boys from the girls, under the age of ten. Designers from Paris to Hollywood imagined a future of equality and androgyny -- within the limits of their own world views, of course.

Explaining it all is where it gets complicated. Unisex clothing was a reaction to most of the gender binaries in fashion: long hair/short hair, skirts/pants and yes, pink/blue. But what alternative was posed, and why? For the most part, unisex meant more masculine clothing for girls and women. Attempts to feminize men's appearance turned out to be short-lived fads, not permanent changes. The underlying argument in favor of rejecting gender binaries turns out to have been another binary: a forced decision between gender identities being a product of nature or nurture. For a while, the "nurture" side was winning. Gender roles were social constructed, learned patterns of behavior and therefore subject to review and revision. Unisex fashions were one front in the culture wars of the late 60s and 70s -- a war between people who believed that biology is destiny and those who believed that human agency can override our DNA. Thanks for listening/reading to my ponderings. Comments most welcome! |

Jo PaolettiProfessor Emerita Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

|