Rompers, jumpsuits, overalls and the like all have a few advantages that make them attractive enough to appear in the fashion pages on a regular basis. They also have aesthetic and practical drawbacks that each generation seems destined to rediscover. To begin with the advantages:

|

What is the appeal of rompers? The original rompers were designed as playclothes for infants and toddlers as a time when the standard clothing for children under the age of five years was dresses. Like dresses, rompers were one-piece, which was desirable for mothers who believed that children could be "spoiled" by too much handling. Compared with ankle-length skirts worn by young walkers, rompers allowed more freedom of movement. That's fine, but we now have many other options, and we no longer believe that babies are harmed by being handled in the process of getting dressed. But the image of romper as a childish style persisted, and has influenced adult casual wear.

Rompers, jumpsuits, overalls and the like all have a few advantages that make them attractive enough to appear in the fashion pages on a regular basis. They also have aesthetic and practical drawbacks that each generation seems destined to rediscover. To begin with the advantages:

3 Comments

Yesterday, February 12, would have been my mother's 90th birthday. In her memory, I decided take a close look at children's fashion in the year of her birth. As the third child born to a young German Lutheran minister and his wife in rural Canada, I doubt if she ever wore any of the fancier styles shown here, but family photos certainly confirm the rules of appropriate clothing for children under 7. Babies from birth to around 6 months: long white gowns, ranging from minimally embellished to elaborately trimmed with lace and embroidery. Babies from six months to a year or slightly older: short white dresses and one-piece rompers. Again, these could be plain or fancy, depending on the occasion and the family's budget and needlework talents. Gender differences were introduced between one and two years, with little boys exchanging dresses for short trousers, often attached to their shirts or blouses with buttons at the waistline. Little girls stayed in dresses, but in an array of colors. Here's a video I created for the occasion: The book was essentially "finished" last spring with the final round of revisions, but I am discovering more and more unanswered questions. Two came up in my Fashion and Consumer Culture course last week: What about pockets? When did button placement become gendered? At first glance, they seem like two more tempting rabbit holes that will occupy the next 30 years of my life. (Look for Pink and Blue 2 in 2312, when I am 92!) Buut both are actually interesting nuances in gender-coding, and worth a look. Right now I will consider pockets.

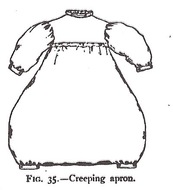

We read a really provocative, insightful article, by Christopher Matthews about the symbolic uses of pockets in 19th century art and literature.* His basic argument was that pockets were a strongly masculine detail, with women's clothing rarely featuring any at all (no surprise to those of us who own pants, skirts and dresses with NO pockets -- in the 21st century!).Then the students were given a variety of garments from our historic costume collection to inspect: a mix of men's, women's and children's clothing. The adult clothing was predictable; lots of pockets for men, fewer or no pockets for women. The guys in the class had twice as many pockets, on average, as the women. The three kids' garments -- two dresses and a suit from the 19th century -- turned out to be the biggest challenge. Because they are undocumented, I nave no idea whether the dresses were worn by boys or girls or both (one was very worn). Both had pockets, but I did not feel confident in using that alone to determine gender. The fact is, I did not look at the absence or number of pockets in children's clothing in my research for the book. In the sources I used, it was not always easy to see them, and it seemed not very useful for "telling the boys from the girls" in the nineteenth century. By the 1920s, when more girls were wearing some form of pants --shorts, rompers, overalls -- the "girl" versions usually did not have pockets, not unlike the women's version. (Something that hasn't changed much.) The unisex versions generally had pockets However, having or not having pockets does influence our behavior -- what we carry with us and how we carry it, even how we stand. (Think of the tendency to jam your hands in your pockets -- if you have them!) I'm actually doing a little follow-up research now on rompers, and this time, I will be looking at pockets. *“Form and Deformity: The Trouble with Victorian Pockets.” Victorian Studies 52, no. 4 (Summer 2010) Ever hear of Amelia Bloomer? She was the American writer and activist who attempted to reform women's fashions in the 1850s by advocating -- and wearing -- knee-length dresses with full matching trousers underneath. She and other dress reformers called it "the American costume", to differentiate it from French-influences fashions, but the popular name "bloomers" stuck. The idea of women wearing any form of trousers was ridiculed and roundly rejected, but bloomers became acceptable for athletic costume, as long as they were worn in public. Fast forward to the 1890s, when bicycles were the latest craze, and young women traded flowing dresses for divided skirts, bloomers and even their brothers' knickers in order to enjoy the new pastime. Once again, the cartoonists and editorial writers had a field day, but this time practicality won out.  creeping apron, 1908 At the same time, a quiet revolution was taking place in children's clothing. Some unknown enterprising person -- probably a mother -- had the brilliant idea of sewing up the hem of her baby's dress, leaving only two holes for the legs. The resulting "creeping apron" (later shortened to "creeper") was initially worn over another dress, like a pinafore, but by the 1910s was worn by itself. A more fitted version, the romper, was introduced for toddlers. Physicians and advice manual writers praised these outfits as being ideal for both boys and girls. In contrast to the reception of trousers for women, the idea of putting little girls in creepers and rompers met with apparently universal approval. There were no anti-romper cartoons, no editorials decrying the masculinization of girls. According to the baby books and paper dolls I have seen, rompers replaced white dresses as the preferred neutral option for toddlers very swiftly, between 1910 and 1920. I say "neutral" because until the 1930s, gender-specific version of either garments were very rare. (Yes, boys wore pink rompers.)

|

Jo PaolettiProfessor Emerita Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

|