|

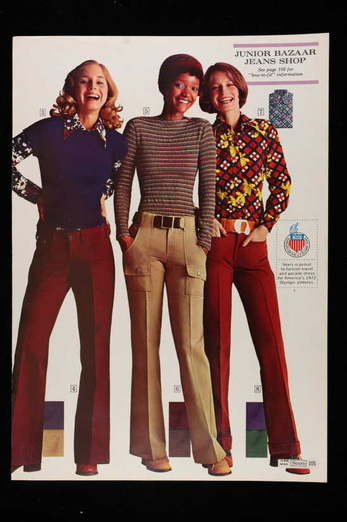

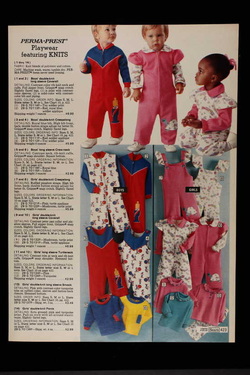

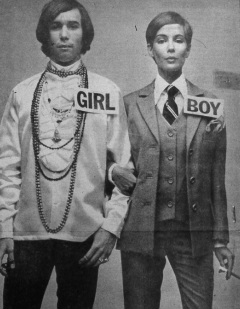

As I finish the chapter on children's clothing, I'm sorting through my images and videos about adult fashions. Here's one you'll enjoy, from an early Soul Train episode. Notice the range of gender expression, on both men and women. A thought: did African American men have more or less leeway in this realm than white guys? My first impression is more, but also that I may be dazzled by the flashiness.  I'm working on a careful description and analysis of the children's styles fro the Sears catalogs, and decided to get reactions from my readers. These images (211 of them!!!) are arranged in chronological order, by year and then season (Spring-Summer, then Fall-Winter). You can view them as a slide show and add comments here or on Flickr. What do you see? (patterns, trends, surprises, memories) Here’s what I detect in the pages of the Sears catalogs from 1962 to 1979: Consistent rules:

From the Perryville, Arkansas school dress code, 1972: After checking in some stores and talking with parents concerning the girls' dress, we have decided to relax the code. We will allow jeans that are made for girls to be worn, providing:  I came across some interesting thoughts on unisex fashion in "Looking Good", published in 1976. The author, Clara Pierre, was writing from the perspective of an industry insider observing what she expected to be permanent changes in fashion. In chapter 10 "From bralessness to unisex", she explains the connection between sexual liberation and unisex clothing as a process of increasing comfort various aspects of sexual identity and expression: "for whatever reason, we began to feel more comfortable first with sex pure and simple, then with homosexuality and now with androgyny" That was then and this is now, as they say. Clearly, some people thought that the culture wars over sex was over, even as it was just beginning. So, I wonder: what happened? I am finally emerging from the end-of-semester editing and grading marathon -- over thirty 25-page papers to read, at the draft and final stages -- and back in research mode for the summer. Bliss! Much as I love teaching, too much time away from writing makes me feel frantic and fragmented.

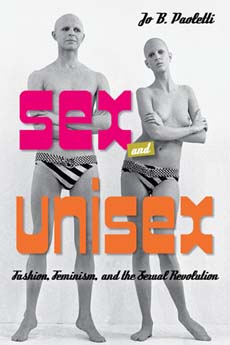

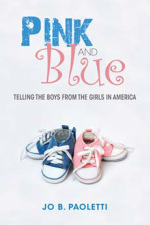

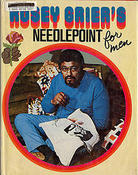

The proposal is still awaiting approval, but the work continues. One of the most frequent questions I get about "Pink and Blue" is about my claim that pink did not acquire its current symbolism until the 1970s. (A bit of explanation: by "current symbolism", I mean not only its meaning, but how powerfully it maintains that meaning regardless of context.) I have been accused of "blaming" feminists for the pinkification of girl culture, because I argue that it was feminist critiques of pink color-coding that helped solidify its symbolic meaning. Now the more I delve into the fashions of the 1970s for my new book, the more I get the sense that something happened in the mid 1970s that super-charged pink as a feminine signifier. Here's today's clue, from the Online Etymology Dictionary: Amer.Eng. Pink collar in reference to jobs generally held by women first attested 1977. I am nearly finished with the proposal for the next book, on unisex trends from the late 1960s through the mid-1980s. Thanks to the fashion cycle and “That Seventies Show”, the superficial outlines of these trends are fairly familiar to the general public. As usual, my intent is to reveal how complicated the movement was (and I chose that word intentionally.).  The unisex movement – which includes female firefighters, Roosevelt Greer’s needlepoint and “Free to be…You and me” -- was a reaction to the restrictions of rigid concepts of sex and gender roles. Unisex clothing was a manifestation of the multitude of possible alternatives to gender binaries in everyday life. To reduce the unisex era to long hair vs. short hair, skirts vs. pants and yes, pink vs. blue is to perpetuate that binary and ignore the real creative pressure for alternatives that emerged during this period. But what alternatives were posed, and why? For the most part, unisex meant more masculine clothing for girls and women. Attempts to feminize men's appearance turned out to be short-lived, not permanent changes. The underlying argument in favor of rejecting gender binaries turns out to have been another binary: a forced decision between gender identities being a product of nature or nurture. For a while, the "nurture" side was winning. Gender roles were perceived to be socially constructed, learned patterns of behavior and therefore subject to review and revision. Unisex fashions were one front in the culture wars of the late 60s and 70s -- a war between people who believed that biology is destiny and those who believed that human agency could override DNA.

The working title is “Sex and Unisex: The Unfinished Business of the 1970s”. Because it’s clear to me from today’s culture wars that the sexual revolution is turning out to be more like the 100 Years War. One of the most iconic works of the unisex era is Lois Gould's short story, "X: a fabulous child's story", a tale of an "Xperiment" in gender-free child-raising. It first appeared in Ms. in 1972, and was expanded into an illustrated children's book in 1978. (The Gender Centre in Australia has the story online.)  Here's a quick summary: A baby is born to two parents who have agreed to keep its sex a secret, as part of a huge, very expensive scientific experiment. They are given a thick handbook to help them navigate future problems, from how to play with X to dealing with boys' and girls' bathrooms at school. While other adults react with hostility, X's schoolmates eventually start imitating its freedom in dress and play. Finally, the PTA demands that X be examined, physically and mentally, by a team of experts. If X's test showed it was a boy, it would have to start obeying all the boys'rules. If it proved to be a girl, X would have to obey all the girls' rules. And if X turned out to be some kind of mixed-up misfit, then X must be Xpelled from school. Immediately! And a new rule must be passed, so that no little Xes would ever come to school again. Of course, X turns out to be the "least mixed up child" ever examined by the experts. X knows what it is, and "By the time it matters which sex X is, it won't be a secret any more". Happy ending. Ah, the 70s! Between this story, Harry Nilsson's "The Point" and "Free to be You and Me", the future looked so clear and bright. What happened? I will be taking a close look at the vision in each over the next week and discussing here, but would love to hear your memories and reactions. |

Jo PaolettiProfessor Emerita Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

|

| Follow me! |